How school leaders can navigate the tumult of year two

Marty Cordova was a promising amateur baseball player in the late 1980s who fulfilled his potential in the 1995 Major League Baseball season by taking home Rookie of the Year honors in the American League. He hit 24 home runs, drove in 84 RBIs, and stole 20 bases. Now, in reading the specificity of that stat line, you might assume that I looked it up on Wikipedia. But, in this, you’d be wrong—as an eight-year-old baseball fan and a burgeoning baseball card collector at the time, I knew that Marty Cordova’s 1995 season had proven a resonant and salutary lesson in my life.

You see, I was certain that on his way to winning Rookie of the Year, Marty Cordova was destined for Cooperstown. In the school yard, I eagerly traded away Ken Griffey Jr. cards in exchange for Marty Cordova rookie cards. I stockpiled them with the knowledge that I was getting in on the ground floor of a Hall of Fame career. I guess nobody had taught me about the “sophomore slump.”

The sophomore slump is a widely accepted phenomenon in which one’s second effort falls short of living up to the relatively high standards of their first effort. This phenomenon has been documented across a number of fields but is most commonly discussed and documented in the worlds of sports and schools.

Marty Cordova never recaptured the magic of his rookie season. By 2003, he was out of Major League Baseball, with his rookie card valued at just $0.35 (less than I’d paid for it). When we compare that to the $3,620 value of a Ken Griffey Jr. rookie card, it would seem that the sophomore slump cost me a pretty penny. But the reason my investment in Marty Cordova was so wrongheaded isn’t that the sophomore slump exists; it’s because it disproportionately impacts people who outperform their peers during their rookie season. A study from Harvard University found that high-achieving rookie athletes are the most likely candidates to experience a dip in performance the following season, with the sophomore slump accounting for more than 12% of the variance in a second-year quarterback’s performance.

I’ll never forget what Marty Cordova taught me. The prospect of a sophomore slump is always on my mind. It’s why I’ve only gone water skiing once: I got up on my skis the first time, managed to make it around the lake without falling down, and will never try it again. It’s also why in June 2021, I left my boss’ office after receiving a glowing end-of-year performance review and immediately opened my computer and typed into Google: “Books on avoiding the sophomore slump in school leadership.” The search elicited zero meaningful hits.

Here I was, statistically on the precipice of a sophomore slump, and I had no resources to avail myself of in order to avoid impending disaster. Comparatively, if you type in “Resources for first-year school leaders” you will get more than 5 billion hits from some of the world’s most well-known educational organizations, including ASCD, NAESP, and EdWeek. At a time when we should be investing more in our young school leaders, it would seem that we aren’t investing anything at all.

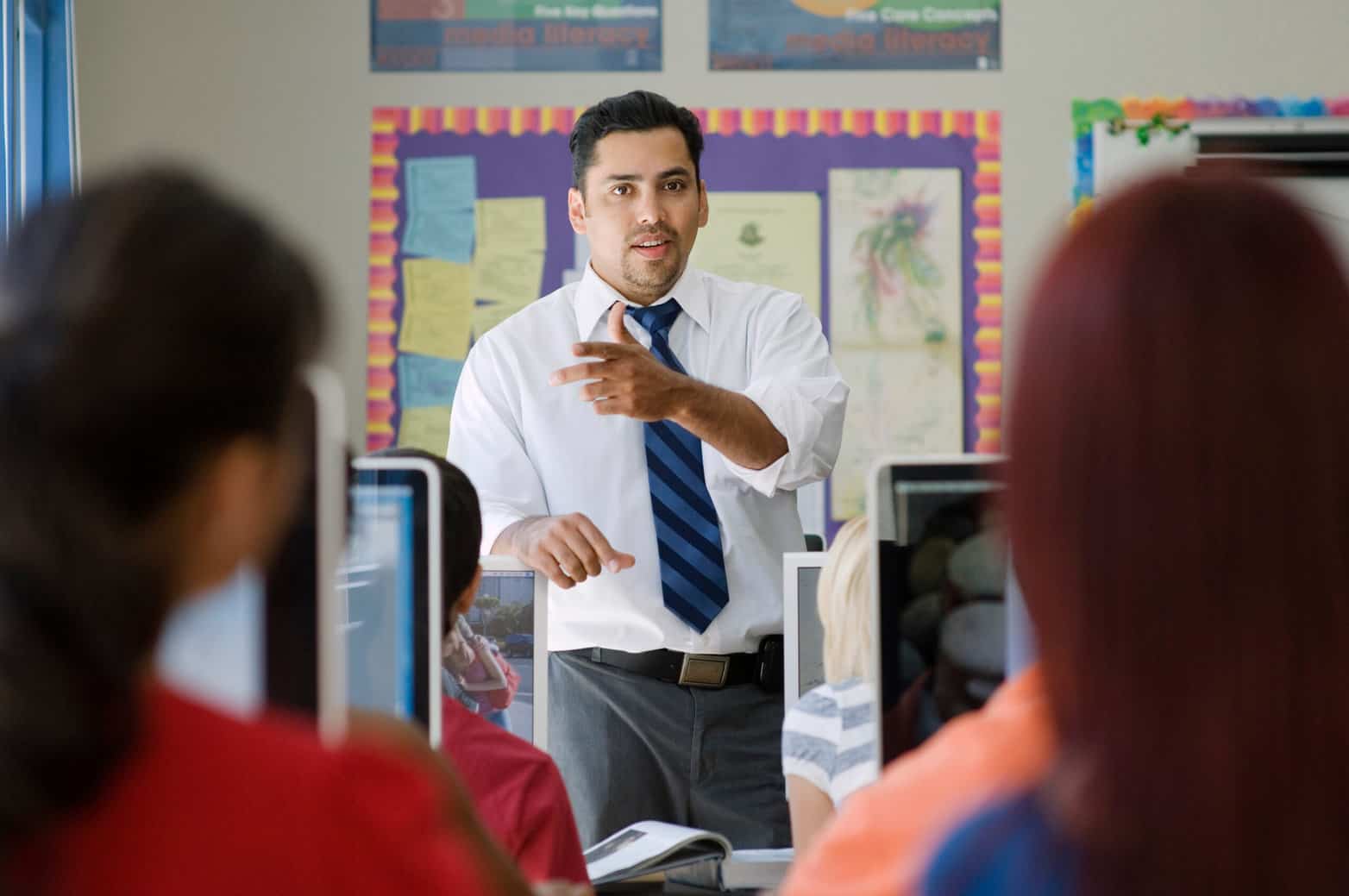

So, here I am. As I finish my second year in educational leadership, I want to share a bit about my experience in the hopes that it will help other young educational leaders to navigate the vicissitudes of the second year.

What to expect:

- The workload grows. Whether it’s starting a school blog, spearheading equity work, or tightening the quotidian systems that guide the day-to-day experience of our students and faculty, the amount of substantive work that revealed itself during my second year caught me by surprise. If you think that the amount of work on your plate is substantial during your first year, just wait until your second year.

- Everything now belongs to you. If you’re like me, you initiated a number of changes during your first year. Naturally, you couldn’t get to everything. Well, all those things that you wanted to change but didn’t are now your responsibility. In your first year, you could say that you inherited an unpopular system or program, but come your second year, it’s your responsibility to change it or be the face of it.

- Your shine turns matte. Famously, presidents have the first 100 days of their administration to enact their keystone legislation. As school leaders, we get a bit more time than that, but not much. After your first year, the novelty of your fresh eyes invariably wears thin. By the start of your second year, your new ideas are old news.

What to do:

- Nobody knows. This might sound like atrocious advice, but it’s liberating to remember that nobody has it figured out. You don’t have all the answers. Educational leadership is one of those deeply imperfect professions wherein you’ll make mistake after mistake irrespective of how long you’ve been doing it. Rather than be self-critical, seek to tap into your PLN or chat with a trusted colleague who can help you to find solutions.

- Mentorship matters. Speaking of, it’s important to find a mentor in your second year of educational leadership. If you didn’t have one already, now is the time to make this a priority. I don’t just mean someone who serves as a sounding board every now and again, but someone who you can send WhatsApp messages to at 2 a.m. because you can’t sleep and can’t figure out what to do. Find someone outside of your organization who has been in your position before. Educational leadership can be lonely and complex, but it’s made simpler and less lonely when you have a mentor.

- Pause is power. As the new Powerade advertising campaign reminds us, it’s important to pause, especially when it comes to change. Lewin’s three-step model of organizational change is instructive in this sense. The successful implementation of change in your first year isn’t necessarily predictive of change in your second year. Once you have made a change, be sure to freeze it to ensure that your faculty doesn’t revert back to their old ways and past habits before the change was implemented. This isn’t to say that change needs to cease altogether, but rather that you need to afford people the time to adjust to the changes you’ve already initiated. Remember: change is predicated on the levels of readiness and trust of your faculty.

- Amplify all voices. If your first year was like my first year, you spent a great deal of it putting faces to names. Unlike me, I hope that you put some thought into what those faces looked like. At the start of my second year, I took time to think back on what voices were represented in my office. Were the parents/guardians in my office representative of a cross-section of my school community? If not, what could I do about it? It’s vital to make sure that you are hearing from a diversity of voices.

In many respects, my second year has been more challenging than my first year. What can you do to navigate the messiness, fun, and frustration of your second year?