Over the last two years, Student Achievement Partners (SAP) has shifted and narrowed our focus from implementing college- and career-ready standards to centering Black students and multilingual learners. As part of that work, some of our team members have been working to understand the impact of a key tool from SAP’s early days: the Instructional Materials Evaluation Tool (IMET). We wanted to know both how this tool impacted the field and what we needed to do differently with the tool in light of our focus on Black students and multilingual learners.

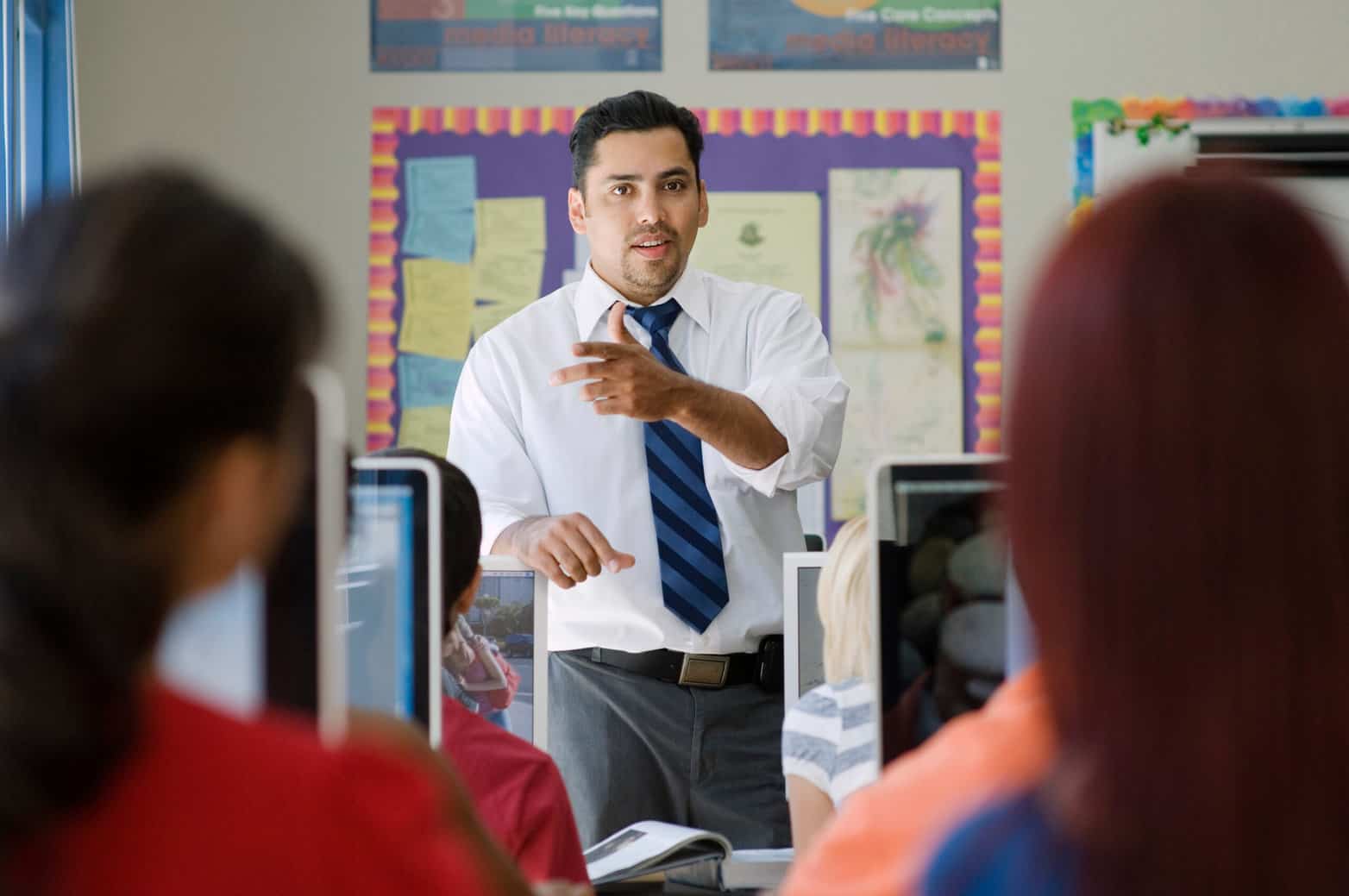

To investigate the impact of the IMET, we started with its users: district leaders who had used the IMET (or pieces of it) to adopt standards-aligned instructional materials in ELA or Mathematics. What was most intriguing to us was that the tool itself was not something that folks wanted to be changed. When we talked to district leaders, we heard that using the IMET to evaluate materials was not what was most challenging about adoption; in fact, leaders who used the IMET felt confident that they had selected standards-aligned materials. Instead of talking to us about how the IMET could be updated to improve selecting materials, users spoke about the challenges of implementation. District leaders we talked to wished that they had done more upfront work to understand the lived experiences of the stakeholders in their districts—their students and their caregivers, their teachers and coaches, their principals and other site-based staff—so that the materials could be implemented in ways that best met the needs of their learning community.

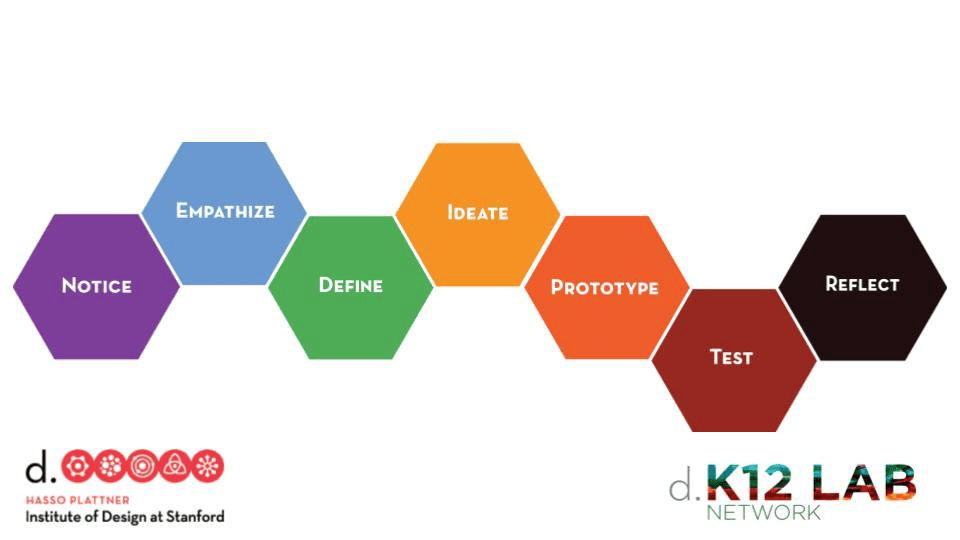

With all of this learning in hand, we set out to design a process to address this challenge. We partnered with the amazing team at the English Learners Success Forum and a truly brilliant group of co-designers from across the country. Through a series of design sprints, we landed on a process that focused on supporting district leaders in gathering data from various stakeholders in order to inform their adoption and implementation processes.

After several design sprints, we had a draft process, initially called a pre-adoption audit, which was designed to help district leaders understand their systems prior to adopting materials. But we knew that creating a tool was just a first step. Since we wanted to understand how this process would be used, we decided to test it with a group of districts that were about to engage in materials selection.

Through a pilot, we were fortunate to work with a cohort consisting of six districts from across the country. These districts tested out pieces of the audit and provided us with feedback about what worked and what needed improvement. We learned from this experience that the tool was not only helpful for understanding what was happening with instructional materials before selecting new ones, but it also helped users understand their system in a much deeper and more meaningful way. In addition, while what they learned would inform their adoption, the tool could also be used at points outside of adoption cycles. The main concern of users, though, was that we needed to provide greater clarity about how to engage in the process.

From this experience, we engaged in another cycle of revision and feedback, and we also made the decision to change the name of the tool to Landscape Analysis. We then partnered with South San Francisco Unified School District to implement the entire Landscape Analysis process in advance of their 2024 math adoption. Through this test, we were able to see the Landscape Analysis process in action and understand how a district could use this process to inform their work in setting a math vision, selecting materials, and building implementation plans to ensure that their Black students and multilingual learners are centered moving forward.

We are incredibly proud of this process because we know we have created a resource that will support district leaders in building teams, collecting and analyzing data, and setting priorities to support their adoption and implementation of instructional materials. Testing has taught us that this resource provides users with perspectives that would not have been included without it, and these perspectives help paint a more complete picture of what is happening in their districts.

And yet, we also are designers. So we know that there is more work we can do to refine the process. In particular, we are excited to delve into revisions that both consider joyful instruction and speak to understanding instruction more broadly. We know that the Landscape Analysis process can be used to understand a school system outside of materials adoption. By constantly refining, we hope to improve on the work of the last two years to build a process that can truly meet the needs of our partners in the field.