What we miss when we narrowly define what “high-quality” means in instructional materials

When I was a fledgling teacher, I looked to organizations like Student Achievement Partners (SAP) for guidance in all things instruction, including materials. In my second year with first graders, my school adopted a new curriculum. At first, I was over the moon! Finally, I wouldn’t have to use the old basal curriculum that I found lacked the challenge and depth my students deserved. Our new curriculum was grounded in the premise that it was designed to “build knowledge” and as a proud nerd, I found myself hyped up to teach units on history and science. The curriculum supposedly had been stringently reviewed and passed with flying colors, so I trusted it. Until I got to a history unit on Early American Civilizations, that is. At that point, I discovered that the label “high-quality” could hide a lot of sins.

SAP played a role in helping to define for the field and for publishers what high-quality materials included (see: Instructional Materials Evaluation Tool), but that definition was focused rather narrowly on alignment to Standards and Shifts. As a result, those elements became the most important things people designed around and looked for in materials. I agreed, and still agree, that they are important. They helped me shift my instruction to focus on knowledge-building instead of isolated skill-building, center complex text instead of leveled readers, and support students in closely mining the text for evidence to support their meaning-making. The ELA Standards and Shifts helped me raise expectations for myself and my students so that my classroom became one that was both fun and rigorous.

Prioritizing the Standards and Shifts, however, meant that other elements—like diversity of texts and authors, the positioning of Black, Indigenous and People of Color within those texts, and the interrogating of dominant narratives—were excluded. And those elements, among others, matter.

As the first year with my new curriculum continued, I realized that even though it checked the boxes for knowledge-building, complex text, and other standards-aligned criteria, under the surface lurked those hidden sins. In that unit on Early American Civilizations, there was a lesson that utilized a letter written by Hernan Cortés to the King of Spain about what he saw in the capital city of the Aztecs. While the objective of the lesson was for students to read closely to learn more about the city, the only attention paid to the impact Cortes had on the civilization was a teaching note on the side of the lesson that read, “Unfortunately for the Aztec people, Cortés’s discovery led to Spain’s conquest of Tenochtitlan and ultimately the end of the Aztec.” Unfortunate indeed.

Despite realizing firsthand that the narratives and historical record presented in the unit were problematic, my initial response was to take it upon myself to adapt it (read: supplement with texts that provide a more truthful, nuanced account). My dad raised me to question everything, and I took that to heart as part of the way I approached teaching. While I continued to find problematic narratives in later units of the scope and sequence, particularly those grounded in social studies, I still championed the curriculum. I knew for myself that I didn’t want to be a part of perpetuating a false, harmful, biased understanding of the past as I built knowledge about it, but the materials were still better than what I had before. It beat trying to write a year’s worth of plans from scratch. But what about teachers who didn’t take the critical stance that I did? What happens when we teach our high-quality curricula without question?

To illustrate that point, let’s take a look at some examples of curricula that have been given a high-quality rating. The review tool used to rate them determines the quality of materials based on three big buckets of indicators: text quality, building knowledge (both included in alignment), and usability. We’ve established that these criteria are important in ensuring students have access to grade-level content and instruction.

On the surface, these look great! EdReports centers indicators related to critical aspects of literacy instruction grounded in the standards and shifts in order to communicate alignment. Teachers should feel confident that those grade level instruction-focused components have been vetted. However, there are other aspects of literacy instruction that these measures don’t account for, one being cultural relevance.

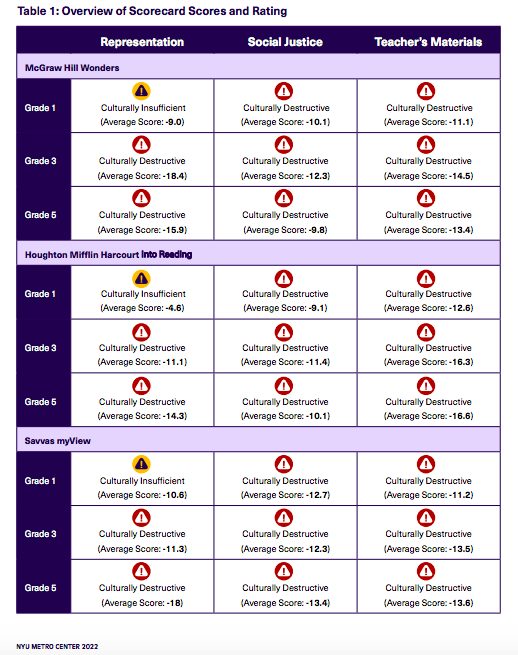

The Education Justice Research and Organizing Collaborative (EJ-ROC), out of NYU Steinhardt’s Metropolitan Center for Research on Equity and the Transformation of Schools, set out to use criteria that expanded the definition of “high-quality.” They developed a Culturally Responsive Curriculum Scorecard that includes three main sections for review: representation, social justice, and teacher’s materials. Their review of the exact same curricula came up with very different results:

- All three curricula were Culturally Destructive or Culturally Insufficient.

- All three curricula used superficial visual representations to signify diversity, especially skin tone and bodily presentation, without including meaningful cultural context, practices or traditions.

- All three curricula were dominated by one-sided storytelling that provided a single, ahistorical narrative.

- All three curricula used language, tone and syntax that demeaned and dehumanized Black, Indigenous and characters of color, while encouraging empathy and connection with White characters.

- All three curricula provided little to no guidance for teachers on engaging students’ prior knowledge, backgrounds and cultures; or reflecting on their own bias, beliefs and experiences.

If you were a teacher told to use any of these curricula, and you didn’t bring a critical eye and the capacity to adapt or supplement the materials, the above points are what you would be perpetuating for your students. Imagine being a student of color in one of those classrooms reading text or listening to your teacher and classmates discuss demeaning or dehumanizing narratives of people who looked like you. Worse yet, imagine believing those deficit narratives tell the truth about who you are. Imagine that experience, year after year.

We have an obligation to ensure that our instructional materials do not perpetuate harm against our students. The definition of high-quality materials needs to expand to include not only alignment to the Standards and Shifts, but also to culturally responsive and linguistically sustaining criteria.

In the fall of 2023, SAP launched an updated definition of high-quality instruction that builds on our historical work and is aimed at describing a vision of truly equitable instruction. The Essential X Equitable (e²) Instructional Practice Framework™ (available here for download) elevates Joyful, Linguistically-Sustaining, and Culturally Responsive-Sustaining practice as equally important to Grade-Level. We’re excited to keep learning about how this could support the improvement of instructional materials in those areas and are committed to being a part of that journey. Join us in the movement towards essential and equitable instruction for all students.