Considering the needs of adolescent readers in the science of reading conversation

One of the best parts about our jobs at Student Achievement Partners is that we get to spend lots of time thinking and talking about literacy. As unabashed #booknerds (we’ve got a group chat and everything), it is wonderful to spend our days thinking and working to support literacy education. For the last several years, this has involved following, and sometimes participating in, the national conversation around the science of reading. But as we’ve debriefed the conversation as a team, we’ve often found ourselves a bit dismayed at the scope of the conversation.

As former middle and high school educators, we value the moments and experience of reading that students own, develop, and multiply. I (Katie) taught middle and high school reading and ELA in Mississippi, and I (Rahel) designed learning and coached literacy interventions in middle and high schools in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., so we think a lot about the unique needs of teenagers. The science of reading conversations happening on social media often leaves us thinking about how this conversation extends to older students who are still learning to read; any middle and high school teacher can tell you that older kids need equitable and essential literacy instruction just as much as their younger counterparts.

Because one thing we know for sure is that challenges with reading have very real consequences for our older students. The Boston Globe recently shed a light¹ on the emotional and mental toll it can take to be an adolescent who has made it to their secondary schooling experience without sufficient reading ability. The article features 17-year-old, M, whose mother describes him as feeling “lost and broken and sad,” as traumatized by his challenges in learning to read.

And that’s where, to us, the science of reading conversation feels lacking: in the essential conversations about supporting our littlest readers and preventing failure from the start, we’ve neglected to talk about what to do for the kids who make it to the upper levels of the K-12 system without learning to read. We completely agree that high-quality early reading instruction needs attention. We just also often think about the thousands of kids like M, who show up to middle and high school every day expected to read tons of text but do not have access to the code to be able to do it.

Which leads to the other thing we know for sure, a LOT of secondary teachers don’t actually know what to do about their students’ decoding and comprehension challenges. I (Katie) certainly didn’t know how to teach kids to decode multisyllabic words or practice their oral reading fluency when I entered my first middle school classroom. Nor could I (Rahel) trust that the numerous literacy intervention programs I supported actually helped older readers improve, because students continued to experience struggle year after year in these programs.

Unfortunately, our experiences aren’t unique. One of the questions we are most commonly asked in our SAP inbox is about how to support older kiddos build their capacity as readers. And in our conversations with secondary teachers, both ELA and in the content areas, we hear a consistent wish for a deeper understanding of instructional practices that can support students in growing as readers and writers.

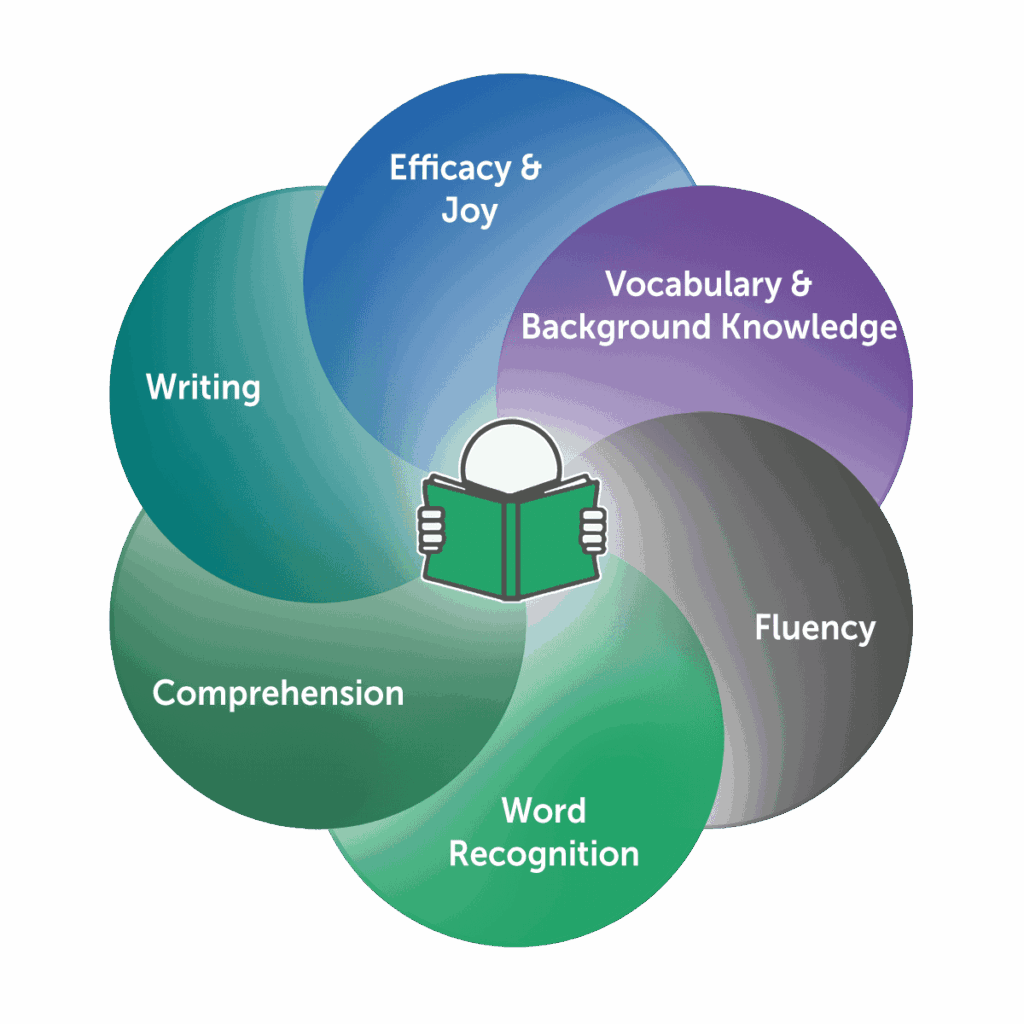

Fortunately, there is an expansive body of research evidence that provides some guidance for supporting reading development. The “Reading Accelerators” can work together to create a picture of literacy instruction that is grounded in student needs and can support older readers in developing their capacity as readers and writers.

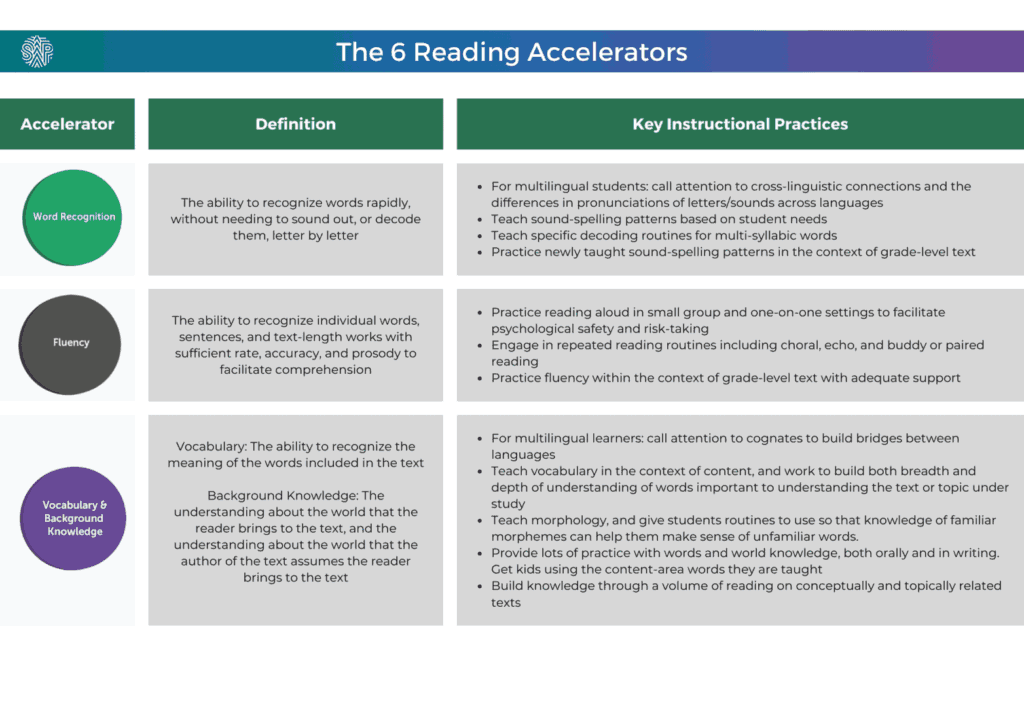

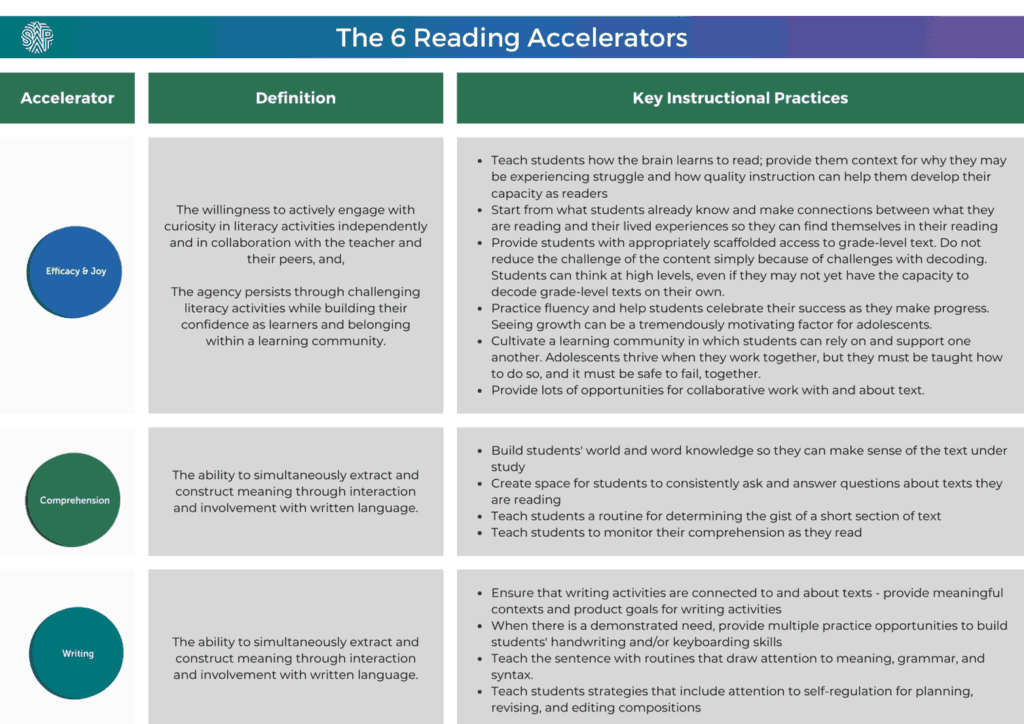

The table below outlines the Accelerators in a bit more detail—providing some context for what they are as well as some of the instructional practices that teachers can implement to make them come alive in their classrooms.

The Accelerators aren’t a quick fix, to be sure. But, individual teachers, regardless of content area, can learn and apply the Accelerators to their practice. And while it will take schoolwide efforts to support students in their literacy, the practices outlined in the Accelerators ensure that students will be supported in their Tier 1 instruction to build their capacity as readers and writers.

We think it’s important to note that the Accelerators aren’t out of line with what we hear in the national science of reading conversation. In fact, they are quite aligned. Where they are different is that they are grounded in the research about what adolescent readers need to accelerate learning. For our older students, we can’t prevent the difficulty; it is there. So we must work on the practices that accelerate and enhance. This means thinking very carefully about efficacy and joy, in particular. It is tremendously important because it acknowledges the emotional baggage that many of our older students carry regarding reading.

I (Katie) know that my first year of teaching would have played out a lot differently if I had access to the Accelerators. And I (Rahel) know that the Accelerators would have helped me better diagnose and design instruction to meet students’ needs. We believe in the power of these tools and hope that, as the science of reading conversation evolves, we can bring more attention to them.

Want to learn more about the Accelerators?

- Check out the white papers, which outline the research base surrounding each accelerator.

- Enroll in our virtual Improving Reading for Older Students course to learn the research behind literacy accelerators that can propel reading progress and practical instructional strategies to support striving adolescent readers.

- Keep in touch with us for future runs of our Improving Reading for Older Students (IROS) course by subscribing to our newsletter.

¹ This article is behind a paywall but available to Globe Subscribers.